ART WORKS AT TULANA

The ART works at TULANA, many of which are by Buddhist artists, contribute to it’s unique ambience, and are the manifestation of Fr. Aloysius Pieris’ life-long project to move away from scholastic theology and its scientific, formulaic “God-Talk”, to a more intuitive theology where the oblique language of poetry and parable, and the evocative idiom of art and music makes theology a spiritual nourishment and inspiration for liberative action on behalf of the People of God.

“The sculptures and paintings of Buddhists interpreting Christianity are based on a missiological principle which is the contrary of the traditional missiology. In the traditional missiology, the Church tells the Buddhist who Christ is. We do the opposite; we ask the Buddhists who Christ is. They tell us who Christ is, and in that dialogue they tell us not only who Christ is for them, but also who Christ is for us in Asia. This is a kind of dialogue with artists who believe in another religion but find Christ as an excellent object of artistic appreciation and of religious devotion. All these people who have made these depictions of Christ and Mary in murals, in clay, or in paintings have given us a message: if we want to speak of Christ, even among ourselves, there is a language to be used. And these Buddhists have given us the language” (Aloysius Pieris)

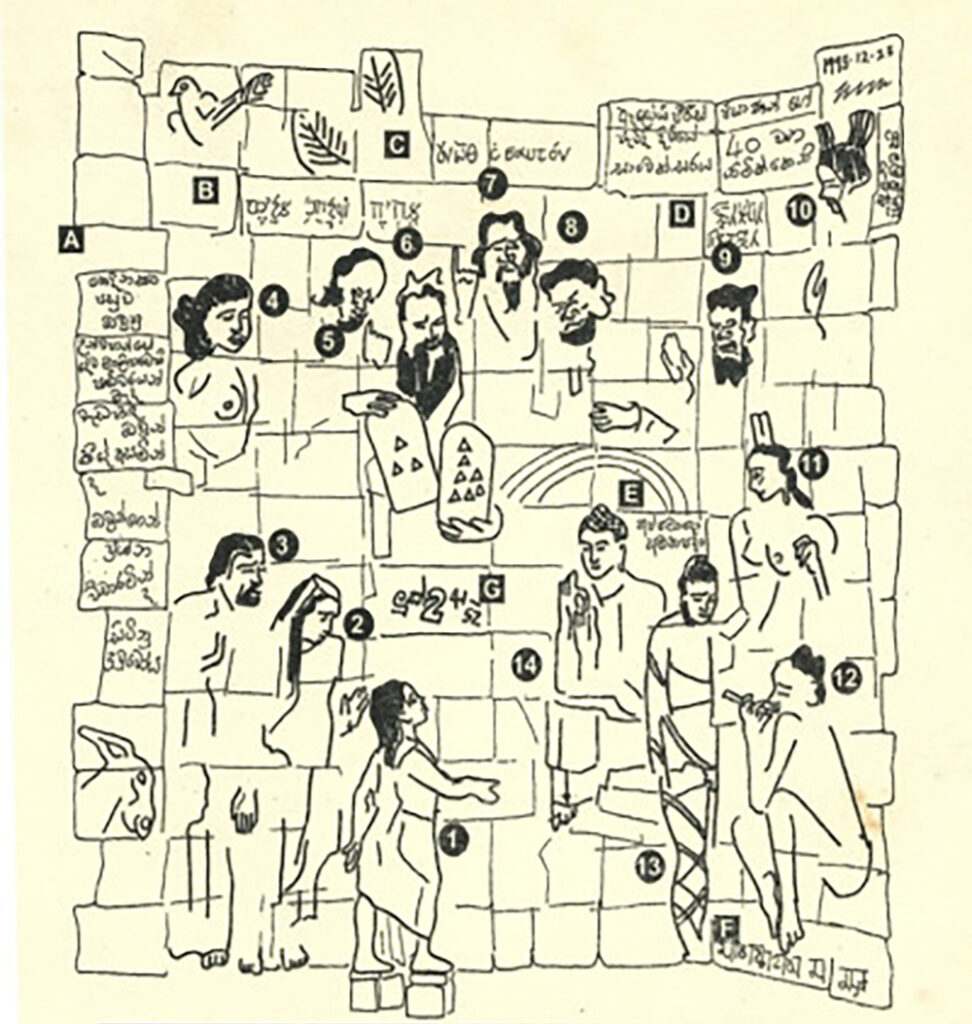

THE TULANA MURAL

(Kingsley Gunatileke)

Based on the New Testament text LUKE 2, 41-52, this terracotta sculpture by one of Sri Lanka’s leading artists, Kingsley Gunatileke, attempts to represent the Tulana ethos of Encounter and Dialogue in the scene of the young Jesus in conversation with the religious traditions of his time.

1. JESUS

2. MARY

3. JOSEPH

4. and 11. The “MAGISTRA IGNOTA” – the unknown women religious teachers of the Western and Eastern traditions.

5. SOCRATES

6. MOSES

7. PLATO

8. ARISTOTLE

9. LAO TZE

10. CONFUCIUS

11. KRISHNA

12. MAHAVIRA

13. Gautama BUDDHA

A. “Three days later, they found him in the temple, sitting among the doctors, listening to them and asking questions” (Luke 2:46)

B. I AM HAS SENT ME TO YOU

C. KNOW YOURSELF

D. FORM YOURSELF BEFORE FORMING OTHERS

E. VIGILANCE IS THE WAY TO DEATHLESSNESS

F. GRIEVE NOT – I WILL LIBERATE YOU

G. LUKE 2, 41-52

Aloysius Pieris;

“This is an interpretation of Luke, chapter 2, verses 41-52. It’s the famous story of Jesus getting lost in the temple. The artist is impressed by the Gospel text—which he has carved here on bricks—that Jesus was found in the temple listening to the past masters, religious teachers, as well as questioning them; the fact that Jesus was a learner and that he was humble enough to learn, and at the same time inquisitive enough to question things, as his mother did even with God.

So here he is gesturing with one hand, with the Buddha right in front. Since the artist is a Buddhist, he has put Jesus and the Buddha face to face, while the other religious leaders are distributed in the mural. So we have here Lao Tse and Confucius; we have below here Krishna, and there is Mahavira, founder of Jainism. We have Moses, founder of Judaism. We have the Greek triad: Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates—rather the other way. And since those who wrote history ignored women, the artist has put women teachers on either side: from the West, because some of the great Greek philosophers had women inspiring them. We have one of them here, in the Western world. And here we have Parvati or whoever you like, a picture of a woman here, to represent the other half of humankind, who were also teachers and learners like Jesus.

So this is the background. Buddha is in the mudra (the manual gesture) of teaching, and there is Jesus listening, and, of course, questioning.

The most peculiar thing is the position of Joseph and Mary. Joseph as usual is silent; a father that is not found in Judaism [of Jesus’ time]; the father is humble , [is in] the background: [he] works, [is] silent, [is] not the dominant type that Jesus wanted to erase from our memory in order to bring his Father to us.

Here we have Mary, who represents the Church and tries to control the Word of God. This is the great temptation of the Church, to control the Word of God.

With one gesture, with his right hand, he is questioning and listening; with his left hand he tells the mother, who represents the Church, “My mission comes directly from the Father. We are [I am] under your jurisdiction, but you have no power over my mission. You are there not to thwart, but to encourage, enhance this mission and stay with me till the end.”

And the artist has written here behind: This is a reflection of what we do here at Tulana. We tell the Mother Church, “Don’t give in to the temptation.” Vatican II says, “Magisterium non supra Verbum Dei est, sed eidem ministrat” (Dei Verbum, #10).It should serve the Word of God; it has no power over it. It represents here that the Church has to respect the mission we have got directly from the Father: i.e., to dialogue with religions. To learn from the past as Jesus did, questioning also at the same time. And this is what we are doing in this house. We tell the Church, we don’t need your permission. We have permission directly from God. But we will be under your jurisdiction. Your function is to help us, rather than to put obstacles to us. This is the general vision that the artist has given us.

[SEE: Jesus and Mary as Portrayed by Buddhist Artists:

short videos of Fr. Pieris explaining the art works

in MONASTIC INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE – web site www.dimmid.org]

PIETA LANKA – 1989

(Kingsley Gunatileke)

Aloysius Pieris;

“The artist has called this Pietà Lanka 1989. That was one of the saddest years in the history of Sri Lanka. The Indian army was fighting the Tamil rebels in the north, rather Tamil revolutionaries, and the Sinhalese army was fighting the Sinhalese revolutionaries in the south. The conflict was between the army and the youth revolutionaries.

The conflict is shown is the background. There is a military tank and a lamp-post. The military tank represents the army, and the lamp post represents the youth militants. Because when they killed someone, they tied that person to a lamp-post and tagged the crime: who did it; why. They put a label. So the lamp-post became the symbol of the insurrection, both in the north by the Tamils and the Sinhalese youth in the south.

This is the background, the conflict which he presents in the shape of Mother Lanka, the youth dying in her arms, and sees in them Jesus in the arms of Mary. It’s again a Christian interpretation of that event. He doesn’t care who killed whom; they are dead. They are victims of something, and they are in the arms of Mary, Mother Lanka.

But there is a little punch to this. This lamp-post is in the form of a cobra. You see here the cobra joins the statue from below. The reason is in the Buddhist tradition, the cobra is an evil force, no doubt about it; but the Buddha tamed the evil force so that when, during his meditation, it began to rain and there was mud all over, the cobra raised him up from the mud by coiling beneath him, with its hood protecting him from rain-water. Which means, this evil force, if it is tamed, can serve us.

So here the artist is trying to give a deep message. If you give the just demands of these youth, north and south, instead of killing them, you tame them, and this force can become a help to Sri Lanka. But a military government can never be tamed. It will always be like that. A student from one of these areas of conflict came and said it was very significant that this military tank is pointed toward the chapel !”.

[SEE: Jesus and Mary as Portrayed by Buddhist Artists:

short videos of Fr. Pieris explaining the art works

in MONASTIC INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE – web site www.dimmid.org]

JESUS AND THE SAMARITAN WOMAN AT JACOB’S WELL – The Water of Life

(from the Gospel of JOHN, chapter 4: 5–42)

(Kingsley Gunatileke)

Kingsley Gunatileke

Aloysius Pieris;

The statue behind us is made of clay. It’s a very difficult material to work on. It took many years to work on it, also to study the scriptural content of this message: the Samaritan woman meeting Jesus at the well, and Jesus asking for water. Here we show the Samaritan woman actually giving the water. There is a symbol here which the artist and I after two years of dialogue and discussion of the scriptural text, came to realize was necessary… as to how the scene should be depicted.

Now actually this probably never happened. John dramatizes the conversion of Samaria to Christ which took place after the resurrection. John has a way of dramatizing historical facts, which brings all the depth of meaning, which normally you don’t see in a narrative. Here it is not a bad woman who happens to meet Jesus, but it is “Miss Samaria” meeting her first love at a well. It’s a well-side wedding, because in the scriptures women who meet men at the well-side end up in marriage. I think John wants to show the remarriage of Samaria to God, to Yahweh. And this is the message that we tried to unfathom reading the fourth chapter of Saint John, the fourth Gospel.

Samaria had five shrines to false gods; it apostatized; it left Yahweh. So this scene brings back the conversion of Samaria in the person of this woman. The woman is shown to be giving water, actually, while Jesus is receiving the water bent down, with hands cupped. Now there is a historical background, an Asian background to this. In India and Sri Lanka, and India still, the low-caste people don’t drink water from a cup when they come, because they pollute your cup. So they pour water and they cup their hands and drink it. Now that is what we want to show here. The artist and I came to this conclusion: Here Jesus reveals himself as Yahweh in his humility; he becomes lower than the lowest. That’s typical of the God of the Bible.

I was inspired by a text in the Psalms [18:36]—in Hebrew—it speaks of Yahweh (or Ha Shem) תרבני ענותך (anwatĕkā tarbēnî). It means: Yahweh, God, you bend down in humility before me, that gesture of humbleness, just to make me feel great. That’s what God does to us. We want to show that: the Samaritan woman, rejected, became someone because God was able to bend down, like a low-caste woman, lower than her, and asking for water and drinking in that manner to show that scriptural text in the Psalms, which the Greeks could not understand. They had another version: “With his powerful hand, he showed his might.” That’s how the Greek text [of the Septuagint], if I remember well, said it. There was power; here there is humility. The Hebrew text I take because it is the text that the Jews still pray with. So it is “Lex orantis; lex credentis.” This is the belief of the people of God, that God humbled herself before the humblest, so that with the humblest they could give us salvation.

Now I think that message is given very beautifully here, and also there is a way in which the bending of Jesus and the cupping of the hands create a new concept of God which is not found anywhere, a humble God, because Jesus proved his divinity precisely by his humility. Our God is humble, and this struck the minds of everybody here, Christian and non-Christian. Here there is a God who is humble, God who joined the sinners and was baptized among sinners, God who in Jesus would be crucified with sinners. His first public act [baptism at Jordan] and his last public act [baptism on Calvary] was just a reflection of God who is humble. This is the message that is given through this statue.

[SEE: Jesus and Mary as Portrayed by Buddhist Artists:

short videos of Fr. Pieris explaining the art works

in MONASTIC INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE – web site www.dimmid.org]

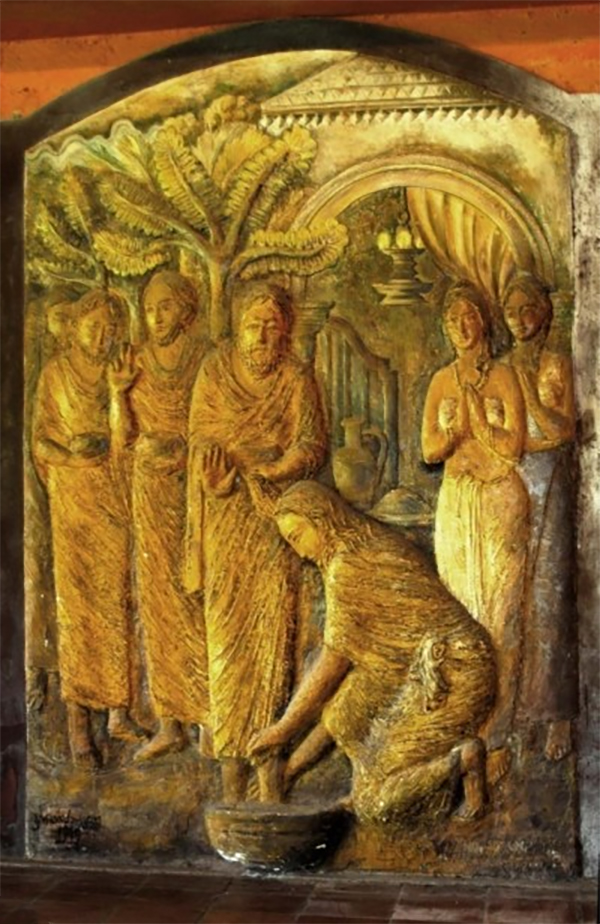

JESUS WASHING THE FEET OF HIS DISCIPLES

(from the Gospel of JOHN 13: 1-20)

(artist: Ven. Uttarananda Thera)

Painter, poet, writer, sculptor, and founder of the Humanist Association of Bhikkhus, Ven. Uttarananda studied at the Brera Academy in Milan. While in Italy, he lived for a short time in a Benedictine monastery, a sojourn he recalls as a profoundly moving experience.

Aloysius Pieris;

“This mural embossment is unique in the history of the world, in the sense that this is the first time a Buddhist monk has ever presented a picture of Christ, in painting, sculpture, or any other art form. This was his first picture of Christ, and with this he began painting a lot of other pictures, some of which were printed in the MISEREOR Lenten calendar [of 2000].

Here he has depicted (his interpretation, of course) the washing of feet by Jesus Christ. He has taken the common meal that the monks are invited to in a home in a normal Buddhist ethos. It’s meritorious to give a meal to monks, and the monks normally come with their begging bowls in their hands. It’s a sign they are mendicants. They don’t have any possessions of their own; they live by begging their food. In Sri Lanka, when they come in procession with their begging bowls for a lunch, a servant of the house normally washes their feet before they enter. And here you see the master of the house washing their feet as they are entering.

The monk is presented through various mudras, dramatic gestures of the hand which are used in normal [classical] drama. The mudra he uses [hand raised, palm facing outward] is “Don’t. I won’t allow it. This is not done,” because the master shouldn’t wash the feet of his disciples; the disciple should wash the feet of his master. That’s our culture. It’s normally the disciples who do all services to the master, not the other way around. Here he has gone against the culture of the place. He is washing the feet.

Then he has put another picture here of two women, one a high class and the other one low class. You can see this from their dress. A person who is familiar with Buddhist temple art can immediately recognize the class difference between the two women.

The other gesture [index and middle finger raised in a “V” shape] means something extraordinarily funny, out of the way, is happening.

This is how, through traditional art forms of the past, the Buddhist monk has brought out the uniqueness of the washing of the feet, even within Christianity, and much more in the Asian culture. It’s a revolution.

There is another difference: the rice and water, with the lamp, which means it’s a supper. Now Buddhist monks never take supper; they normally take their lunch. In a way, the artist has shown that something Christian is happening, but in a Buddhist way. Mendicants are coming, washing of the feet is there (with a revolutionary change), it is in the night (so it can’t be Buddhist monks), and he includes two women. What he brings out is that Jesus is the only founder of a religion who had women in his company, who were not his wife or daughter.

This again shows how a Buddhist sees things that we don’t see. This picture presents a new fact: we cannot understand our uniqueness unless the other tells us. It is always by listening to the other that we know who we are. Our identity cannot be presented by us; it has to be detected by the others. This is what is happening here. A Buddhist is telling us, “Your religion has these unique points: the teacher/master washing the feet, women in the company, at the supper, and there is no class difference.

I told the monk, “You have done something without knowing it. You have intuited [what Paul meant when he said], ‘There is neither male nor female in Christ’ (see Galatians 3:28). Therefore neither should there be in Christianity.” There should not be high caste and low caste, free and slave.

And the third—and this comes out here—in Christ there is neither Christian nor non-Christian (neither Jew nor Gentile). This is a human event. There is no religion here. This is a message to humanity.

I think this monk can grasp the human in Jesus because he belongs to—is the founder of—the Humanistic Association of Monks. He wanted humanism to be the basis of their Buddhist practice. He was fighting against class structure and racial distinction between Tamils and Sinhalese. He belonged to a group of monks who were ready to go to the north and bring justice to the minority.

What we see in Jesus is the attempt of God to teach us how to be human, to be human like God. Here is a picture of Jesus’ humanity. Women and men, high caste and low caste, Christians and non-Christians. Everything is erased. His humanity comes out. “Neither in Mount Gerizim nor in Jerusalem,” neither Samaritan nor Jew (see John 4:21). In his humanity we will worship God.

For me, this is the most revolutionary picture here. There [in the mural of Jesus listening to the teachers in the temple] we had the humility of God; here we have the humanity of God, which Jesus revealed to us. As the medieval humanist said, “If God could be so human, why can’t we be?” Why can’t the Church be? Why can’t all be? This is the message of Christ.

I think the Buddhist monk as a humanist has captured this better than any artist I know.”

[SEE: Jesus and Mary as Portrayed by Buddhist Artists:

short videos of Fr. Pieris explaining the art works

in MONASTIC INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE – web site www.dimmid.org]

‘THE WALL’

An art installation by Chandraguptha Thenuwara

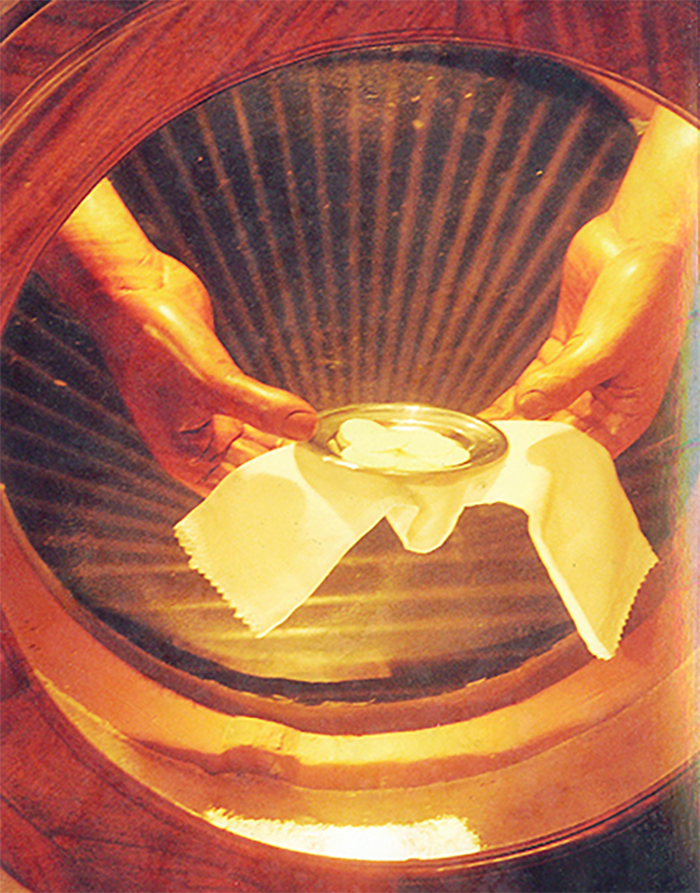

THE WALL is 30 feet long and 7 feet high. Reflective surfaces are placed at right angles at both ends creating the impression of an endless wall. It is built with 10 x 12 inch bricks which were custom made.

Each brick carries an “image” of an actual person who was lost during the war–disappeared, killed, dead. However, the “image” on each brick represents a negative space. The choice of the 10 x 12 inch size also has significance. It is the size of a photograph that is normally enlarged, framed and hung on the walls at home by people once their loved one is lost. When we look at them we feel their presence. The images reflected in mirrors on both sides of the wall signify the endlessness of this tragedy.

THE WALL is a kind of ‘commemoration’ of events which cannot be commemorated. These events are from Sri Lanka’s past, starting with the anti-Tamil pogrom of July 1983. The empty spaces were created by the conflict and the 30 year ethnic war. There are many innocent civilians, security forces personnel, politicians, government servants, rebels, militants etc. who lost their lives over the years of war. If we look at those deaths, not considering their social status or way of living, all are human beings. Everyone is loved by someone.

THE WALL gives an opportunity to the viewer to respond and participate in this ‘commemoration’ and to contemplate the past as well as the future. The viewer can light a candle within the negative empty image. This experience of participation or interaction with this work of art will hopefully create a special kind of social consciousness and a kind of responsibility for the past as well as respect across ethnic divides. It is a small effort towards reconciliation and justice in Sri Lanka.

Chandraguptha Thenuwara

Mary Seat of Wisdom

(Artist: P. D. Ranjith)

Aloysius Pieris;

We have not done anything very revolutionary here. In the early artistic tradition of the Church we know that Venus and Eros, woman and child, were turned into Mary and agape (Jesus). They had the picture of the Madonna based on existing cultural symbols of woman.

Here we have taken the lead from a very common concept of a woman who represents culture, art, music, and wisdom. The title of this sculpture is Mary Seat of Wisdom. It is based on the concept of Saraswati, a goddess of wisdom, culture, and knowledge, and music and art. It’s a combination of everything. In Sri Lanka you never start a drama or a play without a dance in worship of Saraswati. Never. Even in Christian schools we start with this dance. It’s a personification of wisdom, culture, art, everything that is beautiful and holy, and also what is knowledge and wisdom. So it is not simply beauty, it is the beauty of wisdom. It is wisdom, culturally expressed, in various forms of art.

Now we have captured Saraswati, and, in Saraswati, the idea of Mary as a seat of wisdom. I have made a little pun on that word: we call it Prajñāpīṭha. Pīṭha is chair, seat; prajñā is wisdom. And according to Saint Damascene “wisdom” [sophia] was the name for theology. It is a theological faculty that we are looking at, a seat, chair of theology, not just seat of wisdom. It is an artistic expression of the lectio brevis I gave to our philosophate, which bore the name Prajñāpīṭha, punning on the word seat, both as an academic chair as well as a locus where wisdom, Jesus, lives.

Saraswati is normally shown not with the baby, it is shown with a little lamp, sign of knowledge and wisdom, as well as a book opened up. So we have all these signs there to show it is Saraswati, but Saraswati with a message that is new, coming from the primordial symbol of Saraswati found in the mother of Jesus. So it is not an imposition of Saraswati on Christianity. Rather it is understanding Saraswati against the background of a woman who bore Wisdom and presented Wisdom to humankind.

We have taken Jesus out of the womb and presented him in a vīṇa, a kind of a sitar, which she plays. That is in the original version of Saraswati. But we have put Jesus there outside the womb, plucking the chords, while Mary gives the melody. The idea we want to show is a new concept of relationship between God and us. We always use the Thomistic and sometimes Ignatian idea of instrumentum coniunctum cum Deo, instrument joined to God. This instrumental theory is denied here, because in Asia we should be careful; nothing is an instrument in this world. The instrumental theory of using things tantum quantum (so far as it is necessary) to go to God is another version of capitalism, use anything to go to your goal. We don’t use anything.

I rather am impressed by the Greek Orthodox idea of synergy. In a business enterprise maybe one is more powerful and uses the other. But in a love relationship they are equal. They are equal partners in a common mission. God invites us through love to be equal with God in working together, not as an instrument in the hand, just mechanically being used, but a conscious willful participation with our own contribution to what God wants. This is what we bring out here: humankind as represented by Mary, as in the Apocalypse, the whole of humankind, and Jesus, the Lamb of God, the eternal Lamb. One cannot produce the word, the melody, without the other. They work together, synergically. And who is higher or lower doesn’t count, because God has become us, and we have become God. We are divinized; he is humanized. We work together in this way, and he invites us to participate as equals.

So here we see Mary given as an example of how she cooperated as an equal partner with God. [She] had to say yes, agree, and give us an example of this synergic dialogue with God where we are equal partners in a common mission.

[SEE: Jesus and Mary as Portrayed by Buddhist Artists:

short videos of Fr. Pieris explaining the art works

in MONASTIC INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE – web site www.dimmid.org]